-

The Flamboyance and Pizzazz of Miami Art Week 2025

Whitehot Magazine December 15, 2025 Art Basel Miami Art Basel Miami , as one would expect, was a total riot. No matter where you turned,... Read more -

Booming stock market is fueling a mega-billion return to classic art and a backlash to junk

New York Post December 14, 2025 Still, collectors who flew from far corners of the globe to Miami for Basel said they were seeing great success,... Read more -

Memorial Service | Frank Wimberley

Berry Campbell December 13, 2025 Memorial Service Frank Wimberley (1926-2025) Saturday, December 13, 2025, 1 pm Berry Campbell 524 W 26th Street, New York RSVP... Read more -

Lassaw: The Projection Paintings Performance

Norte Maar in collaboration with the Estate of Ibram Lassaw and the Berry Campbell December 11, 2025 Lassaw: The Projection Paintings Performance a collaborative performance of the late 1940s glass slide projections of Ibram Lassaw performed by... Read more

-

The Best New York City Exhibitions of 2025

Hyperallergic December 8, 2025 It's been a big year in New York City — and not just because we (thankfully) got a new mayor.... Read more -

In pictures: a sculptural celebration at Art Basel Miami Beach

The Art Newspaper December 6, 2025 Nora Lawrence, the executive director of Storm King Art Center in New York’s Hudson Valley, shares her favorite sculptures from... Read more -

Don’t Look for This Dealer Duo on the Social Circuit. They’re Busy Creating Markets for Overlooked Female Artists.

Cultured December 2, 2025 Armed with art history degrees, no small dose of resolve, and each other, Christine Berry and Martha Campbell are ensuring... Read more -

The Director of Art Basel Miami Beach, Bridget Finn, On This Year’s Fair

Surface November 25, 2025 Finn says that the galleries remain the heart of the fair. “In the main sector we see strong modern-art presentations—for... Read more

-

Eric Dever | Real, Surreal, and Photoreal

Nassau County Museum of Art November 22, 2025 Real, Surreal, and Photoreal November 22, 2025 – March 8, 2026 NCMA invites visitors into a world where reality is... Read more -

Ida Kohlmeyer | Invocations: Selections from the Permanent Collection

Masur Museum November 20, 2025 Invocations: Selections from the Permanent Collection November 20, 2025 - February 6, 2026 Curated from our permanent collection, Invocations is... Read more -

Mary Henry: A Long Unbroken Line

Portland Art Museum November 20, 2025 ON VIEW: Portland Art Museum 1219 SW Park Ave, Portland, Oregon November 20, 2025 - November 20, 2026 Mary Henry... Read more -

Beverly McIver announced as At-large Member of the North Carolina Arts Council November 19, 2025 Governor Josh Stein announced appointments to boards and commissions. Governor Stein has appointed the following to the North Carolina Arts... Read more

Beverly McIver announced as At-large Member of the North Carolina Arts Council November 19, 2025 Governor Josh Stein announced appointments to boards and commissions. Governor Stein has appointed the following to the North Carolina Arts... Read more

-

Christine Berry, Martha Campbell attend American Federation of the Arts Gala & Leadership Awards, 2025 November 17, 2025 Read more

Christine Berry, Martha Campbell attend American Federation of the Arts Gala & Leadership Awards, 2025 November 17, 2025 Read more -

Observer Art Power Index 2025

Christine Berry & Martha Campbell November 12, 2025 Martha Campbell and Christine Berry, have been selected for Observer's 2025 Art Power Index, recognizing the most influential figures driving... Read more -

WOMEN COLLECTING WOMEN

Panel Discussion November 12, 2025 Please join Berry Campbell, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, and Less Than Half for a panel discussion... Read more -

![Lynne Drexler, Multiple Moons [sic] (1973)](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

How Do You Paint Opera Music? A New Show Reveals Lynne Drexler’s Novel Approach

Artnet news October 22, 2025 Berry Campbell presents 'Lynne Drexler: A Painted Aria,' homing in on the artist's practice during the 1970s. Beginning in the... Read more

-

The Church as Campus for Artists

The East Hampton Star October 18, 2025 “Here and There: The First Churchennial,” the multimedia exhibition now on view at the Sag Harbor arts center, represents one... Read more -

The 10 Best Booths at Frieze London and Frieze Masters 2025

Artsy October 16, 2025 Dedicated to overlooked artists from the 20th century, the Spotlight section of Frieze Masters is a natural fit for Berry... Read more -

Rewilding the Canvas | Eric Dever Interviewed by Mia Funk

The Creative Process October 11, 2025 Eric Dever is a painter on Eastern Long Island—Water Mill, New York. Coupled with his studio garden, recent artist residencies,... Read more -

Frank Wimberley (1926–2025)

October 9, 2025. Berry Campbell is deeply saddened to announce the passing of Frank Wimberley, a beloved figure in the art world. As... Read more

-

HERE & THERE

Nanette Carter at The Church Sag Harbor October 4, 2025 HERE & THERE The First Churchennial October 05 - December 29, 2025 Opening Reception: Saturday, October 4th, 6 PM -... Read more -

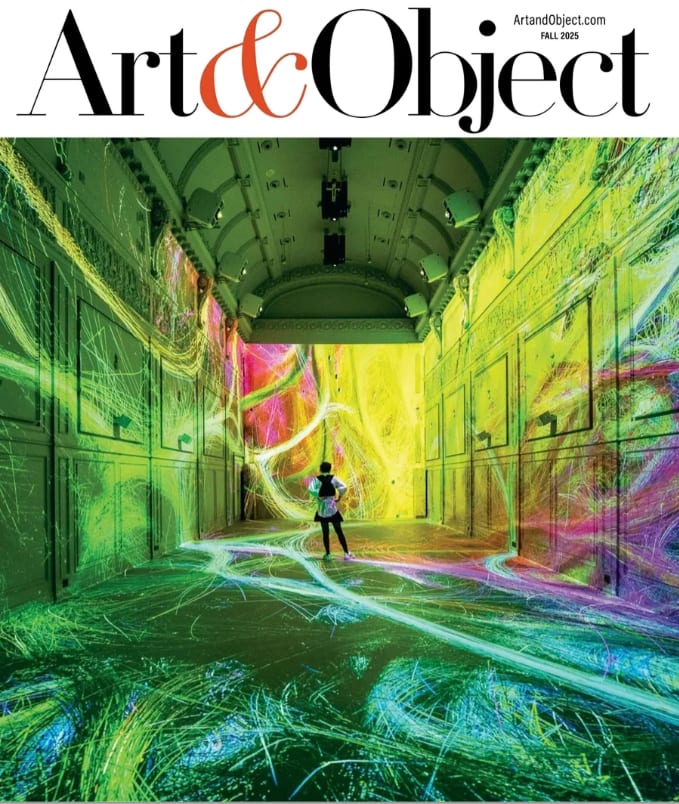

Lynne Drexler

Art & Object | Fall 2025 October 1, 2025 A second-generation abstract expressionist painter. Lynne Drexler studied with Hans Hoffman and Robert Motherwell in the 1950s before launching her... Read more -

Here & There: The First Churchennial In Sag Harbor

James Lane Post September 30, 2025 “Here & There,” the first Churchennial, is a multi-media exhibition highlighting the artists’ residency program at The Church in Sag... Read more -

James Walsh: Relief in Sight

The Sam and Adele Golden Gallery September 27, 2025 James Walsh: Relief in Sight: Selected paintings from 1981 through 2025 September 27, 2025 – February 20, 2026 The Sam... Read more

-

Survey of the Visual Arts: Abstract artworks captivate at Wexner Center for the Arts

The Columbus Dispatch September 27, 2025 Abstract form is explored in Nanette Carter’s exhibition, 'Afro Sentinals.' Carter was born in Columbus and grew up in Montclair,... Read more -

Aesthetic Confessions: Christine Berry and Martha Campbell

The Brooklyn Rail September 25, 2025 Featuring Berry Campbell and Jessica Holmes Thursday, September 25, 2025 1 p.m. Eastern / 10 a.m. Pacific Berry Campbell founders... Read more -

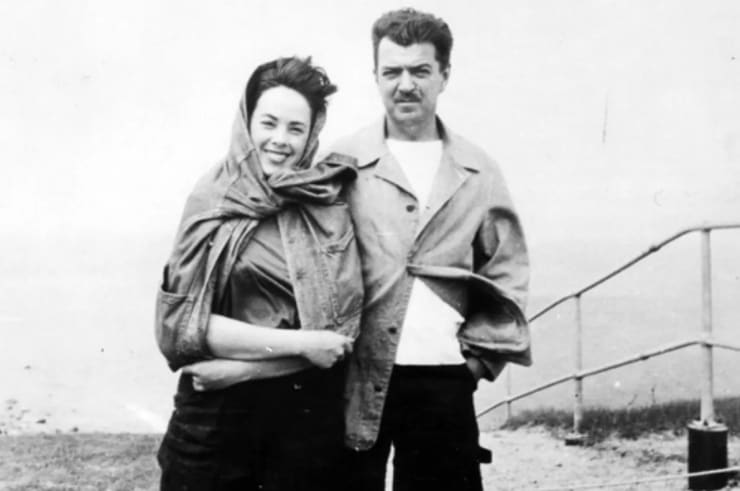

Mercedes Matter

The Brooklyn Rail September 24, 2025 The eye-opening mini-retrospective now on view at Berry Campbell seeks to reclaim Matter’s position as a lodestar in the constellation... Read more -

James Walsh: Relief in Sight

Hyperallergic September 22, 2025 For five decades, artist James Walsh has pushed the boundaries of what paint can do, transforming acrylic into an ever-expanding... Read more

-

Charlotte and Jim: A Personal Reminiscence – Artist Mike Solomon in Conversation with Christine Berry

The Leiber Collection September 21, 2025 The Leiber Collection Sunday, September 21st at 4:00 pm 446 Old Stone Highway, East Hampton, NY East Hampton, New York:... Read more -

Human | Nature: California Zen in Big Sur and the Bay Area

Bernice Bing at The Monterey Museum of Art September 18, 2025 Human | Nature: California Zen in Big Sur and the Bay Area September 18, 2025 - January 25, 2026 Curated... Read more -

Nanette Carter Is a Pioneer of Black Abstraction—and She’s Still Experimenting Today

Artsy September 18, 2025 When she was in high school, Nanette Carter walked into the Guggenheim on a field trip to see the 1971... Read more -

RELIEF IN SIGHT: James Walsh’s Five-Decade Journey Through Paint

Inside + Out September 18, 2025 RELIEF IN SIGHT, on view at The Sam and Adele Golden Gallery (The SAGG) running from September 27th – February... Read more

-

Beverly McIver On View | We Belong Here: The Gutierrez Collection

Cameron Art Museum April 25 – September 7, 2025 We Belong Here: The Gutierrez Collection Cameron Art Museum April 25, 2025 – September 7, 2025 We Belong Here: The... Read more -

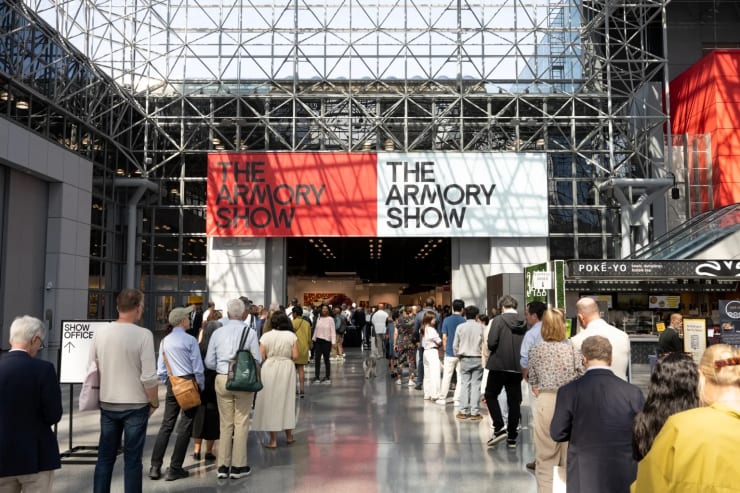

A Brisk Start to the Armory Show Suggests Optimism as the Market Adapts to New Rhythms

The Observer September 5, 2025 Opening day sales point to confidence returning, even as galleries are recalibrating their strategies to align with changing buyer expectations.... Read more -

Jill Nathanson | Instructor Salon 2025

Art Students League September 3, 2025 Opening Reception: Wednesday, September 3, 6–8 PM A tradition that’s more than a century old; the Art Students League... Read more -

12 Must-See Gallery Shows in New York This Fall

Artnet September 2, 2025 From art historical rediscoveries to emerging upstarts, here are some of the standout gallery shows on our radar. The summer... Read more

-

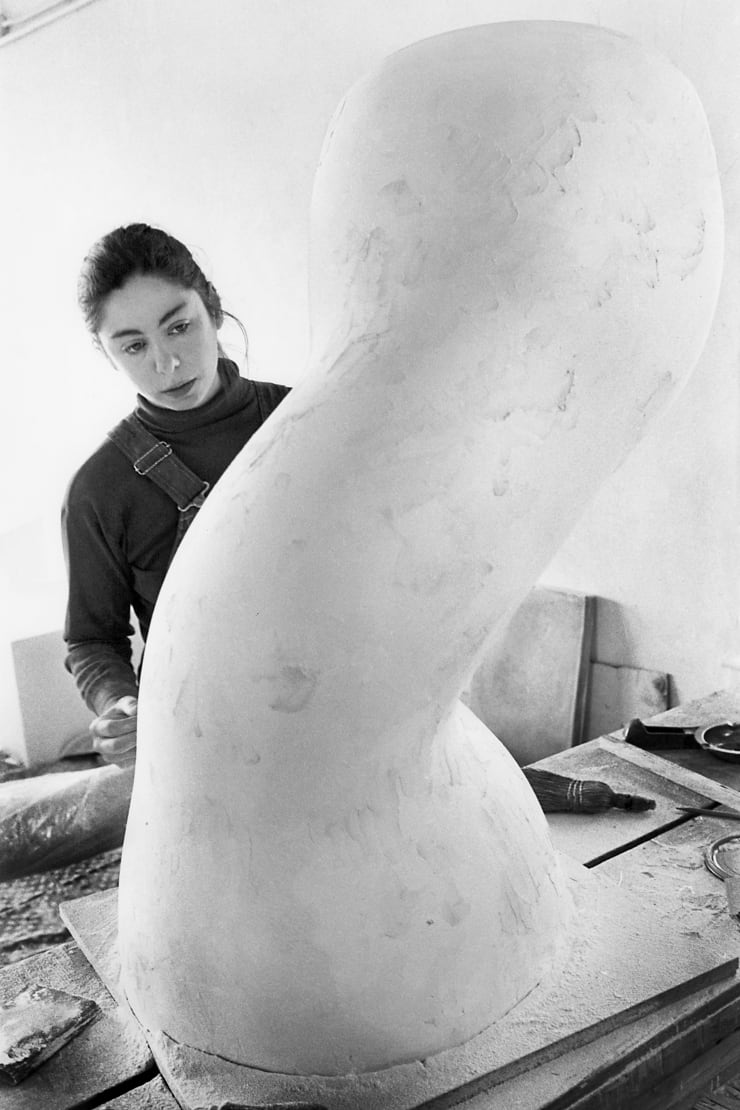

Mary Ann Unger

Artforum September 2, 2025 Mary Ann Unger (1945–1998) was a New York–based sculptor possessed of formidable technical skill and creative vision. She drew upon... Read more -

A Sense of Place

The East Hampton Star August 31, 2025 “Charlotte Park and James Brooks—Of This Place,” an exhibition exploring the connection between two of the East End’s celebrated artists... Read more -

Beverly McIver On View

Bobbitt Visual Arts Center | Albion College August 30, 2025 Beverly McIver Munro Gallery | Bobbitt Visual Arts Center | Albion College August 30 - September 27, 2025 Reception: 5-7pm... Read more -

From Miami to Manhattan: Must-See Exhibitions, Galleries, and Events at Armory Week 2025 Aug 28

Miami Living August 28, 2025 As art lovers from Miami and beyond head north to New York for one of the biggest moments in the... Read more

-

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISTS: THE WOMEN

Female Artists of the Mougins Museum & American Federation of Arts August 23, 2025 FAMM (Female Artists of the Mougins Museum), the only private museum in the world outside the United States with a... Read more -

'Abstract art is universal': Nanette Carter on her new career survey at the Wexner Center for the Arts

The Art Newspaper August 8, 2025 The artist speaks about what drives her practice in anticipation of a solo exhibition in her hometown of Columbus, Ohio,... Read more -

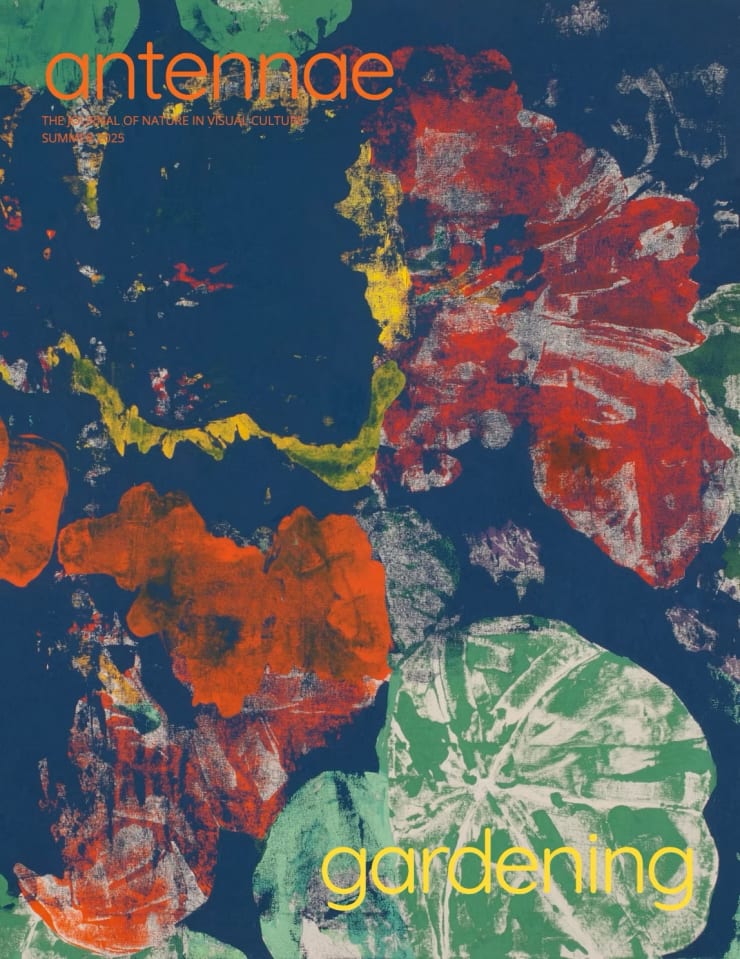

Eric Dever: To see through the garden | ISSUE 67 — SUMMER 2025

Antennae | Journal ISSUE 67 — SUMMER 2025 Rooted in personal experience and ecological observation, this reflection traces the evolving relationship between painting and gardening in the artist’s... Read more -

Charlotte Park and James Brooks: Of This Place

Leiber Collection August 2, 2025 Charlotte Park and James Brooks: Of This Place August 2 to October 5, 2025 Opening Celebration: Saturday, August 2, from... Read more

-

Chelsea Exhibition Reviews: New York Society of Women Artists, Berry Campbell, Rosebud Contemporary and GoCA

Whitehot Magazine August 1, 2025 From my perspective, a great on-site introduction to an artist comes when stepping into a solo show that really sweeps... Read more -

Interview | Nanette Carter by Matthew Deleget: Finding the tools and materials.

BOMB July 30, 2025 In the summer of 2019, my family and I moved to South Orange, New Jersey, after twenty-five years of living... Read more -

Nanette Carter On View | Material Girl

Athens Cultural Center July 20, 2025 Athen Cultural Center On View June 6 - July 20, 2025 Gallery Hours: Saturdays & Sundays 12-5pm First Friday Reception... Read more -

ADAA Chelsea Gallery Walk & Artist-Led Exhibition Tour

Art Dealers Association of America July 16, 2025 Wednesday, July 16, 2025, 6 - 8 pm 524 W 26th Street, New York Please join us Wednesday, July 16th... Read more

-

The Artsy Edit | Rising stars, overlooked greats, and Foundations 2025

Artsy July 16, 2025 Hi and welcome back to The Artsy Edit, a quick guide to what’s happening in the art world this week.... Read more -

Decades Ago, Painter Syd Solomon’s Phillippi Creek Home Became a Magical Gathering Spot for an Endless Stream of Famous Artists

Sarasota Magazine July 10, 2025 Imagine growing up along the shores of Sarasota’s Phillippi Creek , back in the more bucolic 1950s and ’60s, in... Read more -

Rescatan la figura de Lucia Wilcox, la artista que introdujo el surrealismo en EEUU

El Grito | El Confidencial July 10, 2025 Afincada en Nueva York tras la amenaza y los ecos de guerra en Europa, la artista introdujo el movimiento surrealista... Read more -

Eric Dever returns with a new botanical series on view in New York

The Flora Journal July 3, 2025 Berry Campbell Gallery , located in Chelsea, New York, USA, presents Eric Dever: Points of Interest , an inspiring new... Read more

-

Event | In Conversation with Nanette Carter

Montclair Art Museum June 25, 2025 In Conversation with Nanette Carter June 25, 2025 7:00 pm - 8:00 pm Join Ben Jones and artist Nanette Carter... Read more -

Mary Ann Unger | Bodies, by Women

Sheldon Museum of Art | University of Nebraska June 24, 2025 Mary Ann Unger’s 1991 piece ‘Spine’ is on view now in: “Bodies, by Women” an exhibition in the Philip Johnson... Read more -

She Brought Surrealism to America—and Painted Her Own Myth. How Was She Forgotten by History?

Artnet June 20, 2025 Lucia Wilcox rubbed shoulders with Surrealists in Paris, reinvented herself in New York, and created fantastical scenes of jubilant women.... Read more -

Beverly McIver | Exhibition | Kinetic Traces

National Academy of Design June 12, 2025 Kinetic Traces Location: National Academy of Design, 519 W 26th St, Floor Two New York, NY 10001 Date: June 12,... Read more

-

2025 CPAL Annual Conference

Center for the Preservation of Artists' Legacies June 4, 2025 2025 CPAL Conference June 2 – June 4, 2025 Location - The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation 87 Eldridge... Read more -

Artfully Investing: An Art Market Update and Private Planning Discussion

HSBC Event June 4, 2025 HSBC Private Banking Hosts “Artfully Investing: An Art Market Update and Private Planning Discussion” at the renowned Berry Campbell Gallery... Read more -

Ready for Their Reboot: How Galleries Plumb Art History’s Forgotten Talent

The New York Times June 4, 2025 Call it the ‘‘rediscovery industrial complex”: Art advisers and dealers are turning to the past to discover tomorrow’s blue-chip stars.... Read more -

Nanette Carter: Recent Work

The John Hopkins Review | Volume 18, Spring 2025 Spring 2025 'Nanette Carter makes eloquent, inventive collages, ambiguous meditations on her heritage as a Black American and the history of modernism.... Read more

-

Chelsea Exhibition Reviews: Rosebud Contemporary, Paula Cooper, Fredericks & Freiser, Berry Campbell and more

Whitehot Magazine May 29, 2025 Mary Ann Unger: Across the Bering Strait at Berry Campbell (April 17 - May 17, 2025) Monumental sculpture exhibitions are... Read more -

Nanette Carter Returns Home to Montclair With New Solo Exhibition

All of It with Allison Stewart | WNYC May 28, 2025 Nanette Carter in Conversation with Allison Stewart All of It | WNYC May 28, 2025 Artist Nanette Carter grew up... Read more -

In The Gallery: How Berry Campbell Gallery Champions Under the Radar Artists

Whitewall May 27, 2025 Founded by Christine Berry and Martha Campbell, the New York-based gallery is redefining curatorial excellence through scholarship-driven exhibitions, a commitment... Read more -

Artforum Must See | Mary Ann Unger

Artforum Artguide May 17, 2025 Must See Mary Ann Unger Mary Ann Unger: Across the Bering Strait April 17 - May 17, 2025 Reception: Thursday,... Read more

-

Hilma’s Ghost Haunts New York’s Grand Central Station With a Dazzling Mosaic

Artnet May 16, 2025 Their big MTA unveiling came during Frieze Week, and I saw Tegeder and Ray later that night, at a feminist... Read more -

ARTSEEN | Mary Ann Unger: Across the Bering Strait

The Brooklyn Rail May 14, 2025 Coinciding with New York City’s spring art fairs, Berry Campbell Gallery is presenting a thorough and impressive mini-retrospective of Mary... Read more -

Pamela Thomas-Graham in Conversation with Christine Berry on Collecting

NADA New York May 10, 2025 May 10, 2025, 4pm Pamela Thomas-Graham in Conversation with Christine Berry on Collecting NADA New York 601 W 26th Street,... Read more -

A Late Feminist Sculptor Who Plumbed the History of Human Migration

Hyperallergic May 9, 2025 Mary Ann Unger’s massive biomorphic artworks, now on view in New York City, are shockingly prescient and powerful now more... Read more

-

Ahead Of Mother’s Day, Artist Eve Biddle Recounts Growing Up Among The Monumental Oeuvre Of Her Own Mom, Mary Ann Unger

May 9, 2025 When Mary Ann Unger’s Across the Bering Strait debuted in 1994, the sprawling, 34-part installation's raw tactile surfaces and forward... Read more -

Collecting in the Contemporary Art World: A Conversation with Berry Campbell Gallery, NYC

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts May 8, 2025 Christine Berry, Co-Founder of Berry Campbell Gallery in New York City, will share her perspective on the contemporary art world... Read more -

Museum Acquisition | Ann Purcell at Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins May 7, 2025 Ann Purcell (b. 1941) Gypsy Wind , 1983 Acrylic and collage on canvas 72 x 60 inches (182.9 x 152.4... Read more

Museum Acquisition | Ann Purcell at Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins May 7, 2025 Ann Purcell (b. 1941) Gypsy Wind , 1983 Acrylic and collage on canvas 72 x 60 inches (182.9 x 152.4... Read more -

18 Essential Spring Exhibitions to See in New York

Artnet May 5, 2025 As Frieze approaches, New York exhibitions abound—spotlighting major names from Picasso and Leonor Fini to Salman Toor and Rashid Johnson.... Read more

-

Nanette Carter’s Abstract Balancing Act

Hyperallergic May 5, 2025 In this retrospective, the Montclair-raised artist gives the viewer a look at an artistic language that continues to evolve and... Read more -

MOCRA Presents "Meditations" on Art, Abstraction, and Spirituality

Saint Louis University's Museum of Contemporary Religious Art May 3, 2025 “Meditations” explores the intersection of spirituality and the artistic practice of Black creatives encountering ideas within the wide lexicon of... Read more -

Mary Ann Unger Panel Discussion

Berry Campbell May 1, 2025 Thursday, May 1, 2025, 6:30 pm Berry Campbell, New York RSVP Required Panelists: Eve Biddle, Artist, Co-founder of the Wassaic... Read more -

Artist Mary Ann Unger’s Career Was Cut Tragically Short. A New York Show Revisits Her Pivotal Work

Artnet News April 28, 2025 Staged amid a resurgence of interest in the feminist artist's work, the sweeping solo show brings new light to the... Read more

-

Christine Berry, Deborah Spanierman, and Martha Campbell attend the Appraisers Association’s 18th Annual Award Luncheon honoring Jack Shainman. April 25, 2025 Read more

Christine Berry, Deborah Spanierman, and Martha Campbell attend the Appraisers Association’s 18th Annual Award Luncheon honoring Jack Shainman. April 25, 2025 Read more -

Syd Solomon and Kurt Vonnegut’s Wartime Experiences

National Veterans Memorial and Museum April 17, 2025 Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed Extended through June 1 Exploring the dualities of war—concealment and revelation, chaos and order—Solomon illustrates... Read more -

The East End: In the Abstract

Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center April 16, 2025 Highlights from the permanent collection of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center The works featured in this exhibition, highlights from... Read more -

Dallas’ Art Fairs Open With Slow-Burn Sales and Museum Acquisitions That Signal Regional Potential

Observer April 11, 2025 “Growth in vitality is what keeps us going,” Dallas Art Fair director Kelly Cornell said at the press preview, highlighting... Read more

![Lynne Drexler, Multiple Moons [sic] (1973)](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_740,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-artlogicwebsite2161/usr/images/news/main_image/194/drexler_00133_f-copy.jpg)