Lynne Drexler Saw the World Through Kaleidoscope Eyes

February 9, 2023 - Will Grunewald for Down East Magazine, February 2023

Lynne Drexler lived in a white-clapboard house at the end of a long, narrow lane on Monhegan Island, at the foot of a steep slope that climbs to a cemetery, then to a squat granite lighthouse. Her front door creaked on its hinges and opened into a dimly lit hall. Straight through, a south-facing kitchen with big windows provided her a perch overlooking the still water and tall grasses of a bog, which islanders more poetically call “the meadow.” Beyond the meadow were the general store, the stately Island Inn, and, just over a rise, the small harbor where lobsterboats moored and ferryboats docked after their hour’s passage from the mainland.

In her garden, Drexler grew vegetables and flowers — peas, beets, cucumbers, jonquils, zinnias, snapdragons — and, in her kitchen, she made jellies, jams, and pickles. She listened to Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts every Saturday, and she hosted friends in the evenings, a glass of bourbon in one hand and a cigarette dangling from her fingers in the other. She had an encyclopedic mind and often held forth on ballet, Russian history, horse racing. Above all else, from the moment Drexler moved to Monhegan, she painted.

She painted obsessively: the meadow, the woods, the sea, her garden, her line-drying laundry fluttering in the wind. She always worked in series, and if she set up a bouquet on her kitchen table for a still life, she would redraw it and repaint it until the flowers had shriveled. Her studio was a small room in the front of the house, and she worked cross-legged on the hard, wooden floor that was obscured under layers of splattered paint, hunching over her canvases for hours on end.

The attention to work came at the expense of attention to much else. In the kitchen, dirty dishes cluttered the countertops, old mail and dead flowers were strewn about, and fruit flies swarmed, while the rest of the house seemed nearly to sag under the weight of haphazard piles of paintings and drawings. Stretched canvases leaned against each other down the hallway, across the upstairs landing, and against dressers and nightstands in bedrooms. Unstretched canvases and works on paper flopped out of open drawers, draped over chairs, and spilled out from under beds. At one point in the mid-’80s, Drexler guessed she had some 1,200 works in the house, and she kept up her prolific ways until, in 1998, she was diagnosed with cancer.

She died the following year, and only a handful of gallerists and collectors took much interest in her work afterward. By and large, she was unknown. And so it came as a shock to curators, critics, and dealers when, last year, a bidding war broke out over one of her canvases. It sold for $1.2 million, and then another fetched $1.5 million — both going to private collectors. All of a sudden, big spenders around the world were scrambling to get their hands on Drexler’s paintings, and museums and galleries were eager to hang them.

But even as her work has increasingly come into the public view, Drexler remains, in many ways, unknown. More than 20 years of posthumous near-anonymity left few people to tend her legacy, and what remains are fragments of her correspondence, discursive oral histories she recorded for Monhegan’s art museum, and the recollections of surviving friends. The odds were not against Drexler being forgotten altogether. “I’ve always felt deeply within myself I was a damn good artist,” she said in one of the oral histories, “though the world didn’t recognize me as such.”

Drexler was born in Virginia in 1928. Her father was a higher-up at a rail and utility company, and her mother claimed Robert E. Lee and the first two royal governors of Virginia as ancestors. An only child, she was given dance, piano, and art lessons, she rode horses, and she explored outdoors. She was invited to christen a World War II cargo ship. Life, she recalled, was “marvelous.”

But marvelous turned tragic when she was 16, when her father committed suicide. Later, Drexler spoke only sparingly about that time, although she did say she “got sick” around then and, at a doctor’s suggestion, signed up for a painting class. Her life had been altered irretrievably in more ways than one. “Once I picked up a paintbrush,” she recalled, “I was done for.”

In 1949, Drexler graduated from Richmond School of Art. In the mid-’50s, she moved to New York, where Jackson Pollock and his fellow abstract expressionists were having their heyday. Drexler took classes with Hans Hoffmann, whose theory of “push and pull” — how tensions between colors create a sense of depth — was foundational to abstract expressionism. She also studied under Robert Motherwell, one of the movement’s most eloquent exponents.

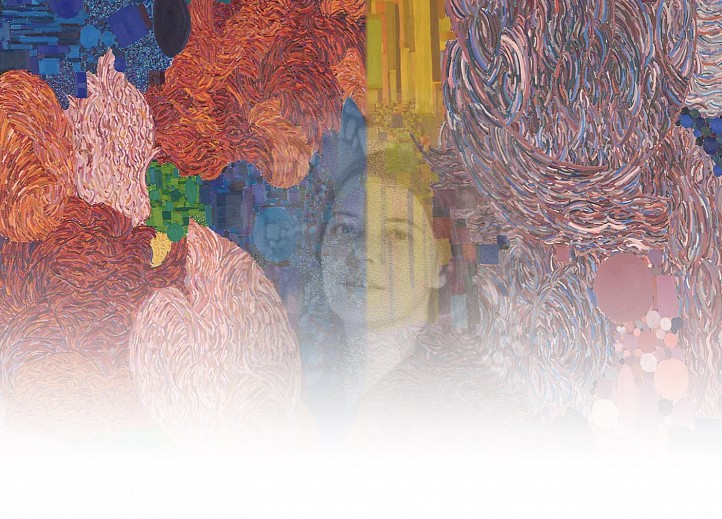

Few of Drexler’s paintings from before 1959 still exist. The ones that do suggest an artist under the influence of the zeitgeist: sweeping, relaxed brushstrokes and tangles of color, but not much trace of the idiosyncratic style she would develop. “I believed in [abstract expressionism] for them,” she said, “but I never believed in it for me.” The reason so few of her early works have survived, she added, is that she destroyed them, and only after that did she feel she had found her own voice. She began using short, swatch-like clusters of brushstrokes that formed veins of colors moving across the canvas, with a near-infinity of subtle gradients. The outcomes were highly abstract, but Drexler was often working from memories of nature, reflected in titles like Fading Lilac, Fog in the Meadow, and Flowered Hundred.

Finding her footing was “difficult and disheartening,” she wrote, but throughout those years, her mother was a doting, concerned, and constant correspondent, consoling her if an exhibition fell through or worrying she was exhausting herself. The promise of a breakthrough arrived when the Tanager Gallery, an artist co-op run by, among others, Lois Dodd and Alex Katz, offered Drexler a solo exhibition. The opportunity was something of a coup for someone with such a slender résumé — Drexler hand-wrote her bio for the gallery to type up, listing her training and a few group shows and scribbling parenthetically at the bottom, “Dull, ain’t it?”

None of her works at Tanager sold, Drexler said, and she couldn’t understand why. But she toiled on, and she hung around the Cedar Tavern, a Greenwich Village bar where Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and other well-known artists did their drinking — the art scene was, by and large, a boys’ club. In 1961, she met avant-garde painter John Hultberg at a party there. He was six years her senior and already established — in 1955, Time called him the “latest darling of modern art,” and Lyndon Johnson later chose one of his paintings to hang in the White House. It was a matter of months until Drexler and Hultberg married, and, in 1963, they left New York for several years for a series of Hultberg’s teaching engagements and residencies, in California, Mexico, and Hawaii. Drexler would come to feel like something of a sidekick, overshadowed by her husband — a “handmaiden to the genius,” she liked to say.

Also in 1963, Drexler’s mother died, and Drexler coped by delving even deeper into her painting, which had again begun to change. Her range of brushstrokes expanded to include skinny slashes and pointillist dabs, circles interrupted her usually angular geometry, heavier applications of paint created rich textures, and clearer suggestions of landscape elements appeared amid all the abstraction, from palm fronds to grasses to tree trunks. Within another couple of years, Drexler was incorporating gracile curves and long, sweeping strokes, her compositions always seeming to find new intensity. “I more often than sometimes go blank when I paint,” she noted. “I just reach for [a color] and it comes.”

By 1967, she and Hultberg were back in New York, living in an apartment at the Hotel Chelsea, where Andy Warhol had recently filmed Chelsea Girls. The building was a bastion for creatives and eccentrics and hard partyers. “Excess was usual, and [Hultberg] was a heavy participant, aided and abetted from time to time by Lynne,” Florence Turner, a friend of Drexler’s who lived down the hall, wrote in a memoir. She also recalled a time she and Drexler suspected their drinks had been spiked with LSD at a party, and they crawled back on all fours to their apartments.

Hultberg’s drinking got worse, and neither he nor Drexler were selling many paintings. Pop art had supplanted abstract expressionism as the prevailing movement, and neither of their styles suited the moment. Plus, Hultberg’s productivity had waned, and Drexler despised doing the sort of self-promotion with dealers and buyers that commercial success more often than not required. “I was not on the political fast track,” she reflected. “I cannot make friends for gain.”

When tenants were hard up for rent, the Chelsea’s owner would sometimes trade for artwork, and one of Drexler’s large canvases hung in the lobby. Hultberg went through several detoxes. At some point, Drexler was prescribed the antipsychotic drug Thorazine, and she attempted suicide. It’s not clear from her elliptical account whether the prescription or the attempted suicide came first, but antipsychotics sometimes affect perception of color and contrasts, and Drexler said, “I couldn’t tell orange from yellow from red. It was so awful. I tried to kill myself, and I damn near succeeded. Because the only thing I had in my life at that time was my work.”

For six months, maybe a year, she quit painting but continued to draw with crayons, since she could read the labels to identify colors. Gradually, her sense of color came back, but most of the ’70s remained, in her estimation, “a really bad period.”

She and John, their marriage rocky, moved out of the Chelsea and into a flat in SoHo. Drexler often picked through discarded scraps of fabric from dress factories for making patchwork pillowcases and other textiles, which she could occasionally sell for a little cash. And for the better part of the decade, the paintings she produced were muted, often almost monochrome. She disliked some of them even as she was making them, and she started to feel she might be through with abstraction. Then, on Monhegan, she found something new.

In 1983, when Drexler and Hultberg moved to Monhegan, some 100 people lived there year-round — mostly lobstermen and their families, although the population always swelled in summer with seasonal residents, visitors, and artists. The latter set ranged over the years from early-20th-century realists to postwar modernists, plus three generations of Wyeths, all drawn by the craggy shoreline or the fine light or the unfussy lifestyle. Usually, though, they departed when the weather turned cold and the days got short.

Drexler and Hultberg had already been making summer visits on and off for 20 years, after Hultberg’s dealer and purported paramour, Martha Jackson, helped him buy the white-clapboard house beneath the cemetery and above the meadow. Jackson provided additional financial aid until she died, in 1969, and her son kept it up through the early ’80s. Then, he informed Hultberg and Drexler that his support was ending, and they promptly gave up paying New York rents.

They arrived on Monhegan with matching green parkas for the winter. Drexler still retained a genteel Virginia accent. Some islanders suspected the two of them wouldn’t last long. Their house wasn’t insulated. Cold was the only temperature for water, which had to be hand-pumped from a well. Old kerosene heaters were unreliable. A small propane generator provided the only source of electricity. When the weather was wet, the roof leaked and the basement flooded.

Hultberg indeed quit the island after the first winter and settled in Portland, eventually returning to New York, but Drexler stayed put. “Spring has been so exciting — the experiencing of all the subtle nuances of it,” she wrote in 1984. “So much I’d forgotten in the years of city living.”

Though they never divorced, Drexler and Hultberg never lived together again. She described the arrangement as “marriage in limbo.” Later, she left a pair of uselessly drooping candles, melted from the sun, standing in her kitchen — she said they were her ode to John, a “limp prick.”

Alone in the house, she settled into a routine, painting and drawing daily through the off-season for as long as the light was strong enough. Friends knew she’d be annoyed if they dropped by before evening. In the warm, busy months, she’d open up her studio, in hope of making sales.

Monhegan pulled Drexler’s art in a fresh direction. For several years before making the full-time move, she took photographs and sketches from the island back to New York for inspiration, and in 1979, she started into her first overtly representational pieces, focused on the woods. “My work is changing,” she wrote after settling into the island, “possibly because I’m so close to my subject matter, which is constantly changing. Nature is never static.”

In a sense, painting actual things wasn’t such a dramatic departure. Nature had always been present in her work, even if it wasn’t obvious. And she built her new representational approach on techniques from her abstract days. Blocks of color interspersed with undulating lines could turn into water. Circles amid tufts of pointillist dabs could form a brushy understory or a lush field. Her skies were full of complex geometry and subtle shifts of shades — and they might be blue or purple or yellow on any given day. As ever, what she put on a canvas was heavily filtered through her own particular way of seeing. “The thing is, it’s always been a variation on a theme,” she said. “I’ve not changed styles so much as I have added and subtracted.” One Thanksgiving, Drexler invited Karen Raynes, a pastry chef at the Island Inn, over for dinner. As a gift, to “color the vision of her world” like the “vision she so often expressed in her paintings,” Raynes brought Drexler a homemade kaleidoscope.

Drexler had once written to a New York friend that, should any dealers come asking about her, “Advise them I’d become a hermit — an eccentric one, and that I come to NYC when provided with orchestra seats to the Met, clubhouse tickets to the racetrack and absolutely no talk of art or the scene.” But Drexler wasn’t really a hermit at all. Tralice Bracy, who later worked as a curator at the Monhegan Museum, met Drexler in 1993. She remembers, when the door first swung open into the house, a commingled aroma of cigarettes, decay, and turpentine. The only light was coming from the kitchen, where a small crowd had already gathered with drinks. Crates were overturned for extra seating.

Other times, Drexler could be found chatting around the woodstove in the island’s library or by the counter at the general store. “She loved to gossip in a very operatic kind of way,” Bracy says. “She enjoyed a good story.” Jackie Boegel and Bill Boynton, who run Monhegan’s Lupine Gallery, used to have Drexler over every Christmas. “She didn’t suffer fools lightly, and she didn’t love just everybody,” Boegel says, “but her friends were like family.”

At one point, Drexler had the notion that maybe she could make money giving art lessons, so she invited a group of those friends, Boegel among them, for a trial run. “It turned out to be hysterically funny,” Boegel remembers. “She sat on the floor, smoking — in her purple, fuzzy bathrobe — and she’d just say things like, ‘You know, you’re either born with it or you’re not.’”

Even though Drexler wasn’t serious about being a hermit, she wasn’t kidding about her disdain for the art scene that had failed to appreciate her. When a dealer asked her to pay a visit to the city, she refused. When some of her work was exhibited in Queens, she wrote, “To me it’s simply another show. Certainly I’ve no expectations of critical acclaim or sales.”

The only signage for Drexler’s home studio in the summer was an old clipboard into which she had reasonably legibly scratched her hours and then propped against some rocks on the roadside. “She had collectors,” Bracy says, “but it was kind of a cult following.” She also simply gave away lots of work, as gifts to neighbors. “Go around the island homes and you’d usually see a Drexler,” Bracy recalls.

As years wore on, Drexler only rarely left Monhegan. On the island, she only rarely left the house, too easily winded and unsteady on her feet. In the house, she only rarely left the first floor, because heating the upstairs would cost too much. She liked to sleep close to her work anyway, so she had a small bed, with a patchwork quilt of her own making, in a small room adjoining her studio. Monhegan had sustained her work, and her work sustained her. She had found something like her very own, very unkempt Giverny, a source of inexhaustible inspiration for her. “There is no isolation in a place like this — impossible to find — but solitude is respected,” she wrote, “and so I had all the time to work that I needed.”

She needed space as well as time. “I think the worst thing an artist can do, once they’ve found their own voice, is stick exclusively with other artists,” she said. “It stifles you. It strangles you. You need the openness of other people and other ideas.” For her, New York City felt like a more insular place than Monhegan Island. “Islands are excellent,” she thought, “for both observation of and participation in life.”

In her will, Drexler split her estate, consisting primarily of her artwork, between Harry T. Bone and Bill and Barbara Manning. Bone, who died in 2012, was a merchant marine who settled on Monhegan, where he and Drexler became close. Bill Manning, an abstract artist originally from Lewiston, got to know Hultberg and Drexler during their time as seasonal residents. When they left their loft in SoHo in 1983, he got a moving truck and brought them to Maine.

The truck, Manning recalls, was quite big, and Hultberg and Drexler needed every square inch. Among the haul were dozens of canvases rolled up and wrapped in plastic. In the early 2000s, he and Bone met to sort through the works in Drexler’s estate, and on a lawn down the way from Drexler’s house, a group started unfurling those rolled-up canvases. Kate Chappell, an artist and friend of Drexler’s, happened to be walking above, by the lighthouse. Looking down, she had the sensation the island was blooming.

These were abstract paintings from before her pivot into representational work. They had been stashed away in her basement, and she hardly mentioned them to anybody. Some were water damaged, others were in good shape, and they were unlike anything Manning had expected to find — the ambitious scale of them, the brilliant play of colors. He called Chris Crosman, then director of Rockland’s Farnsworth Art Museum, who took six for the museum’s collection, gifts of the estate. The Portland Museum of Art took one. Bone and Manning eventually handed over the rest, along with Drexler’s later, representational works, to Michael Rancourt to manage — he owned Portland’s Jameson Modern gallery and represented Manning.

At the Lupine Gallery, in the late ’90s, Drexler’s pieces were selling, on the upper end, in the high hundreds of dollars. Her work continued to pop up in occasional shows around Maine in ensuing years, but not in a way that spiked interest. In 2008, though, Tralice Bracy organized a retrospective at the Monhegan Museum (bourbon was served at the opening), and the exhibition then traveled to the Portland Museum of Art. That publicity might have been an opportunity for Rancourt to introduce more of the work from the estate into the market and keep Drexler’s profile on the rise, but the show coincided with the Great Recession, which had hammered art sales across the country. Rancourt says it snuffed out any momentum with Drexler too.

In 2016, a rising tide started to lift Drexler’s boat. At the Denver Art Museum, an exhibition titled Women of Abstract Expressionism sparked a major reevaluation of underappreciated female artists from Drexler’s era — but not Drexler herself. Still, being a woman connected to abstract expressionism suddenly had market value and critical cachet, even if Drexler personally disliked being classified as a “woman artist” and didn’t consider herself an abstract expressionist for very long. In 2018, one of her large-format pieces showed up in an Architectural Digest shoot at John Legend and Chrissy Teigen’s New York City flat. Elizabeth Moss, who has galleries in Portland and Falmouth, worked with Rancourt on shows in 2020 and 2021 and started to see sales as high as $50,000.

Around then, Saara Pritchard, a veteran of Christie’s and Sotheby’s, was at home one night casually scrolling through Artsy, the online art brokerage, and came across a Drexler painting. Her initial thought was, “Wow, crazy that I don’t know who this artist is.” Soon, she was trying to buy a few of Drexler’s works for herself and looping in some art-buying friends on her newfound interest. She thought Drexler’s paintings were both spectacular and selling for far less than they should, and she thought she could gradually build a market for them. She’d recently done something similar with the late Lee Krasner, who was married to Jackson Pollock — Pritchard helped push her work from the $1 and $2 million dollar range to the $10 million range.

Then, Pritchard heard that the Farnsworth had decided to auction off two of the paintings Manning and Bone had gifted, a pair of the finest examples of Drexler’s early work. Deaccessioning is almost always controversial, and Crosman (who left the Farnsworth in 2005) likened this particular instance to hypothetically breaking up Monet’s Water Lily series at the Musée de l’Orangerie, in Paris. Her paintings, he insisted, are best appreciated together. Pritchard had another concern. For better or worse, auction prices can shape perception of an artist, “so it’s horrible to have a masterpiece come up this early in the process of building a market,” she says. If that first painting, a masterpiece in her opinion, sold anywhere near the Christie’s estimate — $40,000 to $60,000 — Drexler might have been stuck with middling market value and a middling reputation. That’s not to say tens of thousands of dollars isn’t lots of money, but in today’s frenzied art market, prices for van Goghs, Picassos, Cézannes, Warhols, et al., move in increments of tens of millions of dollars.

Behind the scenes, Pritchard rushed to pump up interest, getting serious, deep-pocketed collectors to give Drexler a look. She emphasized Drexler’s overlooked significance to the mid-century canon and, relatedly, the possibility that the still-dawning understanding of Drexler’s place in art history made her work a good investment. Up until then, no Drexler painting had even gone for six figures at auction, but after Pritchard “stirred the pot,” as she put it, those two from the Farnsworth became the paintings that went for $1.2 and $1.5 million and finally focused the art world’s attention on Drexler. (“We were incredibly surprised,” current Farnsworth director Chris Brownawell says. “There didn’t seem to be a sense of tremendous interest in her work.” The museum is using the unexpected windfall to add contemporary artists to its collection.) Now, Berry Campbell Gallery, in Manhattan, represents the estate for Rancourt, and at an exhibition last fall, the show sold out before it opened, prices for canvases ranging from $400,000 to $1.2 million. Presently, the gallery is running a waitlist of aspiring Drexler owners.

It’s become like a refrain,” Jackie Boegel says. “We keep looking up and going, ‘Lynne! Do you see that this is happening?’”

“She’d say it’s about time,” Bill Boynton adds.

Drexler held onto some belief that, eventually, her work would get a fair shake. “At present, we’re not wanted. Only glitz and outrage,” she wrote Hultberg, with whom she remained in occasional touch through their long estrangement — he died in 2005. “But our day will come, even if we’re no longer here.”

Last fall, the New York Times ran a story with a line that Drexler “was painting seascapes for tourists” to make ends meet. Reactions from the people most familiar with Drexler and her work ranged from “unequivocally false” to “bullshit” (the former was Michael Rancourt, the latter a Monhegan lobsterman). “Lynne just had so much integrity,” Jackie Boegel says. “She knew what mattered to her, and she wasn’t cynical about her art. It was her core. She couldn’t sell herself out that way.”

Even two decades after her death, Drexler is a palpable presence on Monhegan. A painting by Alice Boynton, Bill Boynton and Jackie Boegel’s sister-in-law, is titled Memories of Lynne and looks down over Drexler’s house from the hill, with the meadow and the sea in the background. Drexler’s gravesite shares a similar vantage, situated at the edge of the cemetery, directly above the house. Her ashes were interred there after a memorial at the island church, where Drexler, a lifelong Episcopalian, was the congregation’s lay leader, a title she found quite humorous and a position she used to wrest influence from a group of summer people whose religious attitudes she found too conservative (she called them “the regime”), helping to open the church to concerts and other non-ecclesiastical community events.

The current owners of Drexler’s house have kept the kitchen table where she set up still lifes. The same splatters of paint still cover the floor in the room that was her studio, which is where Drexler spent her final days, through late December of 1999, on a medical bed friends had moved there for her. They could tell she was fading as they played a recording of Mozart’s Don Giovanni for her, and she drew her last breath during the opera’s raucous drinking scene. Tralice Bracy was holding her one hand, Harry T. Bone the other. The walls were still hung with Drexler’s final series of paintings, poinsettias and daffodils — improbable bursts of color on a winter day.

“My vision is simply the world as I would like it to be,” Drexler once said. “Any of these highfalutin talkings about painting, that is beyond me.”

Back to News