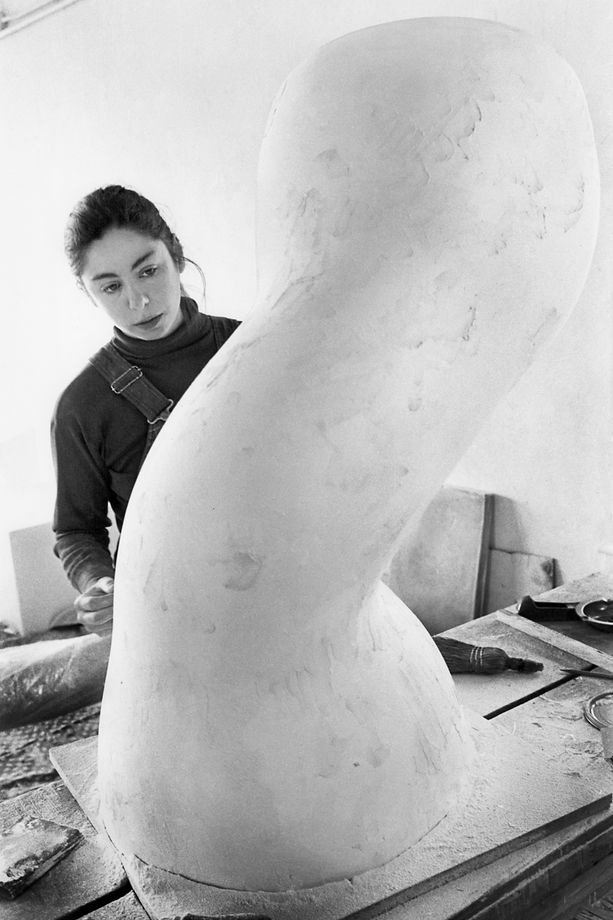

Mary Ann Unger was a celebrated sculptor best known for works that evoke the body, bandaging, flesh, and bone, with recurring themes of growth, regeneration, care, and support. Her oeuvre includes large-scale sculpture, small bronzes, works on paper, and public art commissions.

In her New York Times obituary, Roberta Smith wrote that “[Mary Ann Unger’s] works occupied a territory defined by Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. But the pieces combined a sense of mythic power with a sensitivity to shape that was all their own, achieving a subtlety of expression that belied their monumental scale.”

Born in New York City in 1945, Unger was raised in New Jersey and received an undergraduate degree from Mt. Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts, in 1967, where she first majored in biochemistry before transferring to the studio art program. She received an MFA from Columbia University, New York, in 1975, where she studied with Ronald Bladen and George Sugarman. Her classmates included Vincent Ciniglio, Sylvia Netzer, and Ursula Von Rydingsvard.

In 1975, Unger moved into a studio loft in New York City’s East Village just around the corner from where Jean-Michel Basquiat would take up studio space in the following decade; a community of artists was just beginning to foment there at the time. In 1980, Unger married photographer Geoffrey Biddle, whom she had met while working at the Magnum photographic library when he came in for a job interview. The loft space they inhabited was barely livable upon move in, “raw and filthy, where there had once been a factory that produced perforated metal balls for making tea,” as Biddle wrote. But Unger’s tenacity and ingenuity (including running the meter backwards to help lower bills) helped make it habitable. The hard fight to make a difficult space home was worth it, in Unger’s view, as the 2,000 sq ft floor was large enough for her to live and make increasingly massive works. Biddle and Unger’s daughter, the artist and Wassaic Project co-founder Eve Biddle, was born in 1982, and the loft thereby became home, workspace, nursery, and darkroom alike.

Unger’s early sculptures and works on paper establish themes and reveal interests seen throughout her career: the combination of organic forms with geometric, and a tendency for parts of works to rest against, hold, support, carry, or cradle one another. These load-bearing works were deceptively simple, but their underlying structures were finely engineered. Frequently, the pieces require no hardware and instead balanced on one another securely utilizing Unger’s meticulous, mathematical construction. Her early work was included in exhibitions at PS 1 in 1977 and the Aldrich Museum in 1978.

Mary Ann was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1985, the beginning of a long entanglement with the disease that would ripple through her life and work until her death. Between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s, she simultaneously worked on both publicly commissioned artworks and gallery-based solo exhibitions. Among these works was Communion at Sculpture Center, New York, as well as exhibitions at the New Jersey State Museum, the Klarfeld Perry, and Trans Hudson Galleries. In 1989, Unger received a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant and would again in 1995; she was also a resident fellow at Yaddo in 1980 and 1994.

In the late 1980s, her works Temple and Beehive Temple were acquired by the Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art, Ursinus College and the Sculpture Gardens, Lehigh University, respectively. In 1989, she was commissioned by the City of Tampa to create the public artwork Wave. Her work, Ode to Tatlin, was commissioned by the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College in 1991. In 1985, she and Biddle purchased a house in upstate New York that became a secondary refuge for her work. There she had nature to reflect on and contend with as well as space in which to unfurl. Later, she would also spend summers in Mt. Desert, Maine, a location that influenced works such as Maine Wishing Stones and several watercolors.

In 1992, Unger received a Guggenheim Fellowship and mounted the solo exhibition Dark Icons at Klarfeld Perry Gallery, New York. These two achievements punctuated an abundantly productive period during which illness was a frequent visitor, a fact made evident by the show’s themes. As Joan Marter noted: “With their durable armatures, the Icons allude to sculptor herself: her strength and determination to survive; her will that overcomes all misgivings or doubts.”

Critics often spoke of Unger’s work in this period as having two distinct voices: public works that “are volumetric, brightly colored architectural structures, rendered in a kind of geometric formalism” and private works that “are solemn, heavy abstractions rich with intimations of mortality and loss” (George Melrod, Public Art Review, 1993). Motherhood, too, became a theme, reflected most poignantly in Pieta/Monument to War. Unger was also an unabashedly feminist artist. Her name appears on the infamous “Guerrilla Girls Identities Exposed!” poster of 1990. Though Unger herself was not a member of the Guerrilla Girls, her inclusion situated her in a feminist activist role within the art world alongside a host of women artists of the age.

Unger’s works have been reviewed in the New York Times, Sculpture magazine, Art in America, and The Village Voice, among many other publications. Critics and writers have tended to emphasize the preoccupation with illness and death made manifest in her work, though posthumously and retrospectively it’s clear that other, often opposing, themes also run throughout. In her assessment of Dark Icons, Marter wrote that Unger’s work was “heroic... daunting... a spiritual quest attempting to demystify the body through rituals associated with death.” However, as Douglas Dreishpoon notes in a catalogue essay for Sculptural Heroics:

“Never one to deny the coexistence of forces that affirm as well as threaten life, Unger’s sculptures embody both conditions. Her work can be seen as a projection of her own trying circumstances. But it also aspires to another dimension beyond the personal, to a more universal plane where the object mirrors something of ourselves.”

Michael Kimmelman wrote in the New York Times, “Mary Ann Unger's ‘Ode to Tatlin,’ at Queens College, adds to an otherwise drab and incoherent stretch of campus a monument at once airy and grand.” Proof of life, in other words, in the midst of dead space. “Here neither life nor death are ‘touched-up’ for viewing,” writes Carla Harriman, about Unger’s piece Pieta/Monument to War, though she could also be speaking about Unger’s life and work more broadly. “Nothing distracts from the primary site and sights of our physical experience of each other,” Harriman adds. “The physical, spiritual, and psychological disease, sufferings and desires of the body are trapped, exploded, and transformed in Mary Ann Unger’s work.”

In 1994, Unger mounted her most ambitious project to date, the sculptural installation Across the Bering Strait at Trans Hudson Gallery in Jersey City, New Jersey. Comprised of 34 large scale sculptures, along with sound immersion and highly calibrated lighting design, the work made a forceful impact, the themes of which seem prescient. Unger wrote in her artist statement:

“‘Across the Bering Strait’ is about the past, but it is also about the present. Populations are shifting all over the world today, refugees from battle or oppression, hopeful immigrants and adventurers pursuing dreams. They carry their nationalities and their cultures with them just as they carry their possessions. We may have our hopes for an information superhighway and our dreams of an interconnected world in the technological twenty-first century, yet it is still the movements of peoples that makes us aware of each other around the world: migration is arguably the strongest force towards the creation of a global village. Just as it made the world larger thirty thousand years ago, it is still people moving, migrating, and even literally walking, that is making the world smaller today.”

Vivien Raynor of the New York Times observed that, “Any way it is viewed, the installation packs a huge punch” and that the work’s “blend of the erotic and the macabre represents a climax [in Unger’s work] that had been building since the mid-1980s.”

And yet, as her work grew in scale and deepened in significance, so too did the cancer which had first arrived in 1985. Unger died on December 27, 1998, in the loft, with her husband and daughter by her side.

As is the case with many women artists of the 20th century, interest in and appreciation for Unger’s work has increased posthumously and in retrospect. Indeed, as Kara L. Rooney at Brooklyn Rail observed, “there is much still to be learned about this earnest and exacting feminine force” whose works “reveal an inquisitive and astute hand.” Jane Panetta, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, calls Unger a “pioneering female sculptor.” This expanding view of Unger’s legacy also serves to highlight that she worked in other media, namely works on paper. “Drawing is a natural extension of Unger’s creative process,” Drieshpoon wrote, “and she does it as a matter of course. There’s a distinct poetry to her works on paper.”

A 15-year retrospective of Mary Ann Unger’s work took place at the McDonough Museum of Art in Youngstown, Ohio, in 2000. Unger’s works are held in numerous private and public collections, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washintgon, D.C.; the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania; the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York MOCA Los Angeles, California; and the High Museum of Art, Georgia among many others.

In 2022,

Mary Ann Unger: To Shape a Moon from Bone curated by Horace Ballard, was on view at Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) featuring Unger’s works in conversation with those of her daughter, Eve Biddle, who is an alumna. Central to this show was the exhibition of

Across the Bering Strait and

Shanks, which WCMA acquired in the early part of 2021. Called a “long overdue exhibition” by Cassie Packard in

Frieze, Jackson Davidow asserted in

ArtForum that “this stunning exhibition sets the stage for a critical reassessment of her ever-vibrant and undeniably relevant work.”