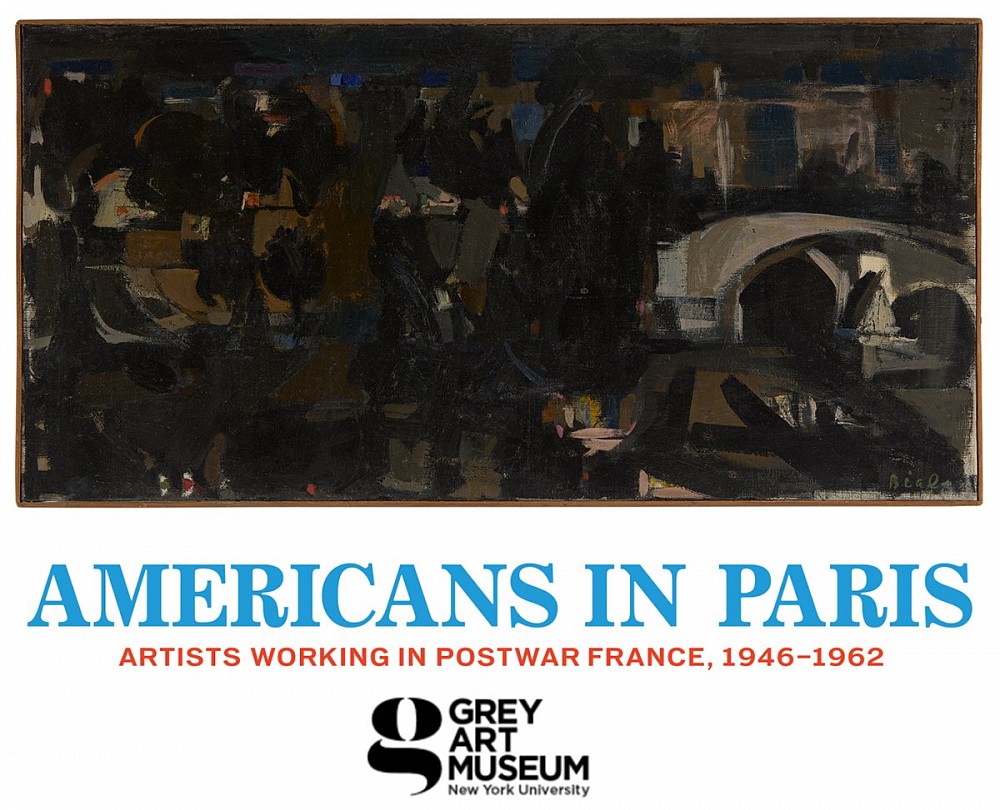

Janice Biala (1903-2000) La Seine: Paris la Nuit, 1954, Oil on canvas, 18 x 36 3/8 in (48.3 x 92.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

AMERICANS IN PARIS:

Artist Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962

March 2-July 20, 2024

The Grey Art Gallery

New York University

100 Washington Square East

NYC

Following World War II, hundreds of artists from the United States flocked to the City of Light, which for centuries had been heralded as an artistic mecca and international cultural capital. Americans in Paris explores a vibrant community of expatriates who lived in France for a year or more during the period from 1946 to 1962. Many were ex-soldiers who took advantage of a newly enacted GI Bill, which covered tuition and living expenses; others, including women, financed their own sojourns.

Showcased here are some 130 paintings, sculptures, photographs, films, textiles, and works on paper by nearly 70 artists, providing a fresh perspective on a creative ferment too often overshadowed by the contemporaneous ascendency of the New York art scene. The show focuses on a diverse core of twenty-five artists—some who are established, even canonical, figures, and others who have yet to receive the recognition their work deserves. A complementary section dubbed the “Salon” combines works by French and foreign artists that the Americans would have seen in Parisian galleries or annual salons, alongside examples by compatriots who likewise spent at least a year residing in France during this time.

While the U.S. art scene was dominated by the rise of Abstract Expressionism, Americans working in Paris experimented with a range of formal strategies and various approaches to both abstraction and figuration. And, as the esteemed writer James Baldwin—a longtime French resident—saliently observed, living in Paris afforded expats the opportunity to question what it meant to be an American artist at midcentury. For some, Paris promised a society less constrained by racism and the exclusionary power structures of the New York art world.

American artists also encountered undercurrents of nationalistic tension, as French critics sought to maintain Paris’s artistic preeminence. By 1962, the year that concludes the exhibition, many felt that the once-inspiring atmosphere had diminished. That same year, Algeria achieved independence from France after many years of demonstrations and riots, and, ultimately, war. Many Americans opted to return to the U.S., which was experiencing a burgeoning civil rights movement, and in particular to New York, where there were more opportunities to exhibit, due in part to the rise of artist-run galleries. Others chose to remain abroad. Whether they returned or remained in Paris, the Americans’ encounters with French collections, artists, critics, and gallerists significantly impacted the development of postwar American art.

Read More >>