Larry Zox Review in Artforum

September 1, 2017 - Donald Kuspit for Artforum

It’s hard to categorize Larry Zox’s painting, though many have tried. In 1965, his work appeared in the exhibition “Shape and Structure,” organized by Frank Stella and Henry Geldzahler, which positioned the artist’s work amid hard-edge Color Field painting and Minimalism. A year later, Lawrence Alloway included Zox’s art in the show “Systemic Painting,” implying the work is best understood as an example of repetition and systemization, then supposedly the new “in” thing. This exhibition at Berry Campbell, however, demonstrated that Zox’s work betrays these categories. The eighteen pieces displayed (four small works on paper, fourteen on canvas) don’t have the reductive look of Minimalism—their colors don’t form a uniform field—and their structures can’t be regarded as systems. The repetitions that occur in them tend to be limited, giving them an odd inconclusiveness, and with that a peculiarly absurd, irksome quality.

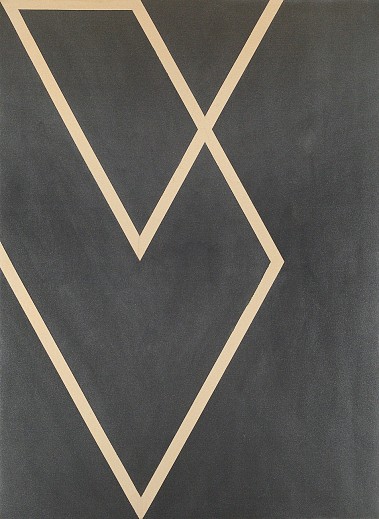

Take, for instance, Cordova Diamond Drill, 1967, with its five crisscrossing yellowish lines against an austere black field. (There is also a stray horizontal line, which cuts halfway across the upper border). The composition is cool and stately, with an authority that suggests a kind of order. Yet the figure promised in the title never materializes; instead, we find a near-diamond that is missing one of its sides. The diamond is all but destroyed, rendered as an aborted, flattened form—a substanceless shape, more alluded to than convincingly present. In the Dictionary of Symbols (1969), Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant describe the diamond as “the preeminent symbol of perfection,” admired for its “hardness, translucence and brightness” and for its “immutability.” But here it is black, imperfect, mutable; Zox distorts us only with its aura. Similarly, in the works on paper, all 1964, Zox perverts the square. Its sides are squeezed in, and bands of color move across its flat surface.

All the works in the exhibition seem cunningly contradictory—geometric abstractions with a spontaneous expressive twist, a sort of edgy uncertainty. In Untitled, 1963, an asymmetrical white triangle cuts into a broad yellow plane; this backdrop is imperfectly rectangular, boasting a curvilinear upper edge and an off-kilter lower edge. Similarly, the diagonal line in Diagonal IV, 1967–68, is made up of two misaligned parts and cuts through the composition like a fault line. A similar “cutting” diagonal appears in the diptych Multi from Zone 1, 1965. The eye sits on that rift, trembling as the tectonic plates in the parallelogram seem to clash. The colors and shapes support and emphasize the diagonal’s contour, keeping it from breaking the painting apart, even as it does. There is an air of suspense to Zox’s abstractions, all the more so because the forms and colors never exactly harmonize. This air of irresolution, this inconclusiveness, demonstrates that geometry can convey disquiet, not only purity and transcendent idealism. Zox finds error in the tools of precision.

Back to News